|

As always it is here that adventure begins. To the North, the Gods of Olympus who evoke the secondary school benches, the blackboard and Greco Latin translations. To the East, the biblical Gods who recall the catechism and the village church. To the West, the mangled carcasses of Rommel's tanks complete their rusting in the sands.

To the South, there is nothing!

No cultural debris, nothing but the mysterious spice trail which loses itself in the unknown void.

The Suez Canal!

Gloriously inaugurated in 1869 by the Empress Eugenie herself, it was built thanks to the astonishing energy of viscount Ferdinand de Lesseps whose enormous bronze statue erected on an island in the center of the waterway, way sawn of at the base and thrown on the scrap heap in 1959 by Colonel Nasser.

|

Drawings by O.Gonet

After the canal, going down to the South is ideal. The system of winds is more or less controlled by the Monsoon from the North which dominates in the Indian Ocean.

A beautiful sea with a lot of wind behind. A very slow pitching and the lovely sound of the waves which break into foam as they pass by the boat beneath a sky of astonishing brightness. All sails have been hoisted and there is nothing more to do on board because absolutely nothing is happening except the passing of time.

Very far away to starboard on the tide race of endless waves, one can make out the coast of Africa: Raz Abu fatama, marsa Halaib, raz Nadarba, marsa Umbeila. A blurred feature is a gulf, another which grows thicker is a headland.

On the maps, the tropic of Capricorn is at hand. There is no more spring or autumn. The wind from the North stirs up the burnt desert sand and illumines transitory needles of yellowish light on the horizon.

And one day, we put in for the first time into a real tropical lagoon. Cautiously the boat slipped through an opening in the coral reef. Just at the entrance, the big swell from the open sea is breaking heavily. Beyond that it is calm. There is practically no more wind and no more waves at all. The water is green and deliciously fresh and transparent. The beach is yellow, red and brown. The desert drunk with heat flickers under a metallic sun. The boat with almost no wind, moves very slowly, floating over its shadow which can be seen gliding over the sea-bed.

Atuana in Red Sea

As soon as the sun goes down, it is necessary to drop anchor and not move any more because the big slabs of coral unknown to the nautical charts can suddenly appear level with the surface.

So one enjoys the enchantment of the tropical night. One listens to the little wet sounds which the fish make when they move on the surface, to the mysterious creaking of the wood in the boat and to the heavy breathing of the waves which out to sea are crashing on the coral reef. And then there are the glimmers from beyond the grave which the multitude of plankton light up, and the multitude of the stars and the moon above a track of light which shimmers on the wavelets of the lagoon.

Directly the sun rose, the incongruity of our presence in the vast landscape simply hit us in the face. In this wonderful silence and wide open-air, the feeble sound of our voices or of a creaking pulley or the rattle of a chain and the unpleasant smell of the caulking or of paint or from the kitchen, all seemed to be rather sour in this immense mineral world.

* * *

Under the water, one discovered another world altogether. It was just an unbelievable luxuriance. The delicate many-colored coral brings to life an abundance of paradise fish as if made of porcelain. Angel fish, doctor fish, trumpet fish, parrot fish and clown fish. Beyond the reef, the big sour-faced groupers red or brown, softly enter and emerge from their holes. In the dark blue, not very far away are the sharks. The tiger sharks, hammer headed sharks, blue sharks. The silvery barracudas and the big tunny. On the surface, the timid turtles.

And all that lives, eats, browses, attacks, sleeps, swims, in shoals, in families, in couples or solitary, hidden in the seaweed or just in the water, in holes or in the depths, in the coral flowers or just above. It is lemon, yellow, bright red, emerald green, pearl grey, ebony black. There are shapes of musical instruments, of hair, of volutes, of sharp points of knife-blades. It can be fuzzy, flat, starry, lacelike, spotted, brilliant or mat. And it is all that at the same time, seen in the small or the big, from near or from far.

Putting ones head out of the water one looks in bewilderment at a completely desert-like earth. Not a plant, not a beast around for hundreds of kilometers. At two steps from the maddest exuberance, a man lost without water in the desert dies in two hours crushed by the sun as if beneath the feet of a giant.

* * *

We have navigated and worked for eight months along the Red Sea coasts. We have lived through thousands of adventures which I have told about in another book. However one day it was necessary to think about returning to the Mediterranean. After such a long go of tropical navigation, the ship needed repairs. At that time, the only big city which was really modern, was Beirut. It was there that we had to go. The time of year did not seem to be worse than any other. The North wind all day long and then the flat calm after six in the evening.

During the first week, all went very well and during the daytime we went up against the wind. Sometimes on one tack, sometimes on the other. When at nightfall the wind dropped, we continued to advance with the motor.

For this long voyage without any scientific work, we had lessened the crew. We were not more than five, counting Béchir, the cook. The ATUANA is not a big boat. Thirty odd tons. Five crew were quite enough. Unfortunately we had not foreseen that on entering the gulf of Suez, between Sinai and the Jubal channel, the sea was going to show us a face which she sometimes assume like a witch.

One evening, the horizon filled up with a real wind, more than 100 kilometers an hour and straight at us. It was only the beginning of the storm but the sea was already hollowing out extremely short waves and tornadoes of sand hid a really vicious sky.

In the face of this solid wind and of waves like walls the boat hardly advanced at all. We had reduced the canvas to practically nothing, a fore-staysail, afore sail and just a little bit of the big sail. That deadened the shocks and lessened the rolling.

|

Oil painting by O.Gonet

Then with sails and motor, we were making long zigzags across the whole width of the gulf. In the daytime the battle was very hard, but it was at nightfall that the real nightmare began. We had to get our bearings in the darkness and know when to veer before touching the reefs near the shore. The nearer one went to the coast, the more did the night become filled with sand. The sextant was useless and the radio-gonio too inexact. Nothing but judgment and common sense remained. It was necessary to watch for the slightest change in the sea, the noise, the force of the waves and whatever else makes a sailor think he is approaching a reef. In short one had to find a way out, while fighting all the time with ones arms against the sails that were banging and against the waves that were crashing over the deck and against the wind which forced us to crouch, so as not to get carried away and against the movements of the boat that was dancing all over the place.

A single one of these zigzags for ten or twelve hours of struggle and that gained us only 15 miles towards the North. Less than 3O kilometers for a night of battle.

And the time passes. One day and two nights and that only made it worse. A sportsman's pleasure at the beginning gives way to sad and wet tiredness.

My turn to sleep comes and I go to collapse on my bunk, but I am woken long before time. Max, my old friend of adventures and voyages, has just had an accident. In making fast a halyard at the foot of the big mast, he has received straight in his face, the mainsheet of a staysail which has been ripped from top to bottom. The poor man has lost an eye!

We must get to land and find a doctor. But in such weather there is no question of risking by night a crossing of the unknown reefs which fringe the whole coast. It is absolutely essential to wait for daybreak.

The chart indicates that there is a petrol-working site at Raz Garib, 35 kilometers to the South. Going down before the wind while day is breaking we stand to lose what it took us so much effort to gain.

At Raz Garib there is a good weather anchorage but on that day the whole gulf was being swept by spray and by waves more than three meters high. Impossible to put the dinghy in the water, it would immediately be carried away.

My unfortunate friend, in spite of his damaged eye, is having to swim ashore. I see his head which recedes while dancing up and down in the enormous waves. There is no other way out.

Luckily he will find on the beach an American geologist who has come by chance to see the neighboring petrol well in a small private aeroplane. He took him straight away to Cairo. Then by an airline, he arrived a few hours later in Zürich where a surgeon saved his eye.

I did not know all that until much later. For the moment our fight against the storm has only begun. To put the lid on it I have just been informed that there is no more fresh water on board. A badly placed tap has opened accidentally and all our water has drained into the hull. Apart from various alcohols, all that remains for us is a mango syrup which is so bad that we have been keeping it for months, without finding anyone to drink it. For the rest, I remain the only experienced seaman on this big boat caught in the storm.

But its not the moment to start grumbling. One hour after our arrival at Raz Garib, the anchor chain has broken. We have to put to sea immediately, leaving behind the biggest of our anchors. Just as the boat is drifting straight at the coast, I dive into the engine room. Luckily, the motor starts at first go. A few seconds later and we would run aground on the beach among the big breakers. And the big zigzags begin all over again. The wind whistles madly in the rigging. One after another, the waves crash and pour over the deck from the bows to the stern.

During the day, I feel that the ship is getting heavy. It responds less well to the helm. It recovers more slowly from the terrifying heeling which the gusts of wind force it to make. A glance into the storeroom explains it, she is full of water. The pump in the hold doesn't work any more. Impossible to repair it at sea. From now onwards, pumping must be by hand, one hour every four hours.

At nightfall, the motor also begins to cough. At ten o'clock, we are only on three cylinders, at midnight only on two. The situation is becoming really critical. We must get in somewhere to repair it. I have practically not slept for 36 hours.

The motor is turning over pretty badly, at a quarter of its strength, until daybreak. Then it definitely stops.

There is nothing more than the immense noise of the sea.

I veer round, not without difficulty because with so little sail, the boat is scarcely maneuverable and I set the bow straight for the coast. The chart indicates a sort of bay largely open to the sea but in which I can hope that the strength of waves may be less violent.

Arrived at the most favorable part of this bay, I drop the anchor. That is when with horror it becomes evident that instead of gripping, the anchor is atrip on the bottom and does not hold the boat which slowly but inexorably drifts on a wall of reef.

All appears lost, when finally the anchor grips on to a little chunk of coral placed like a vanguard just at the foot of the reef. One or two more yards and it would have been the end.

This mooring will not hold for long. At each wave, the boat rises and falls in more than five yards of height. The rollers form just under the stern. In the hollow of the waves, one can see through the water the rock standing like a wall. Stretching out an arm one could almost touch it. It is necessary to get away from here as soon as possible.

But it is impossible as long as the motor wont function. Each time that the mooring is stretched, it is the 30 tons of the boat which pulls, with, in addition, all the force of the wave which crashes on to it. It is unthinkable that only the four of us could pull on the Hauser and raise the anchor by hand. We need the electric winch but for that, we need the motor.

The breakdown comes from the oil feed. In this kind of engine, one air bubble getting into the piping, which brings the heavy oil from the reservoirs, is enough for the pumps which inject the fuel into the cylinder to uncap and cease to function. When the reservoirs were being shaken and stirred up in all directions by the storm, it is not very surprising that an air bubble got into the pipe.

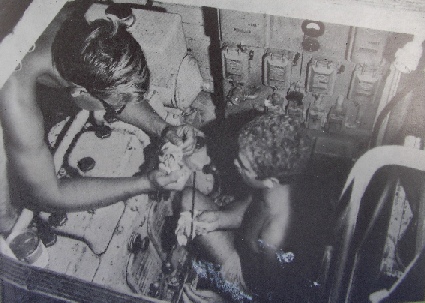

Therefore this piping has to be emptied, all air bubbles removed and the pumps reprised. In the calm of a harbour, this job would take twenty minutes. But here, with the lurching of the boat, I have to crouch down not to be thrown against the motor and the exhaust box which is still burning hot.

To crown the misfortune the bench is upside down and all the tools strewn around the engine- room or in the hold full of greasy black water.

In the filthy oil which splashes my face and completely soaks me at each movement of the boat. I grope for the pliers which I need. There is nothing else to be done it has to be this way.

Having found the pliers, I notice that the waste-pipe joints have been tight for so long that it is impossible to undo them in a normal way.

At that I reached the depths of despair.

To quiet down and think it over, I go up on deck to have a cigarette. I am covered with black and viscous grease but the brutal wind straightens out my thoughts. I notice also that the boat is once more nearing the wall of coral. It has got to be done quickly now. The catastrophe wont be long in coming.

With an enormous sledge hammer, I hit with all my strength the handle of the spanner that holds the cursed joint. It moves suddenly and is undone, and we are saved.

An hour later, the motor is running normally, with its help, we take up the anchor without too much trouble and leave that lethal spot.

It is high time to do so, evening is falling. Twenty minutes more and we would have been in total darkness to tackle the narrows.

Then the big zigzags start again. I have still not slept and the state of tiredness of my three companions is no better.

It is a time of revulsion and sea-sickness but no matter, so long as it finishes.

But gradually, imperceptibly, towards midnight things are quieting down. At the beginning this is very subtle. At the helm one seems to feel that the ship is navigating a tiny bit more easily It holds to the course better, the speed increases There is at least a quarter of hour interval between two of these violent gusts that make us heel over so dizzily. And then nothing very serious for half an hour. The following gust is definitely weaker. The trough of the waves diminishes.

Two hours later, the whole thing is finished. It is flat calm. There is still a swell but its over. Even a few stars are visible. The sea gets back its smell of good weather.

We have succeeded and we are through, all at one go the terrible nervous tension breaks. We rock with laughter. Allah is great. The warm happiness of feeling among friends and safe and sound with one's two feet planted on a firm deck is intoxicating.

We treat ourselves to drink, straight from the bottle, our last bottle of whisky.

Victory, the sun is rising in a beautiful blue sky, over an almost calm sea.

Calling in at Suez at last! After so

much space and wind. There are the palm-trees and the cars and the kitchen

smells and the blocked lavatories.

Calling in at Suez at last! After so

much space and wind. There are the palm-trees and the cars and the kitchen

smells and the blocked lavatories.

The boat is well moored to the bitts of the old English yacht club. But the English have gone long ago and their club beyond dilapidation is finally falling into ruins.

On the lawn reverted to dead and cracked earth are a few ridiculous armchairs distinguished, but lame on the missing foot. The tables have disappeared. The fine swimming pool for water polo is empty, nothing but a lot of old paper, turds and torn motor tyres.

In a corner, a bar has been built up with a few old petrol drums. A waiter, superbly dressed in a black coat done up with string, offers tea to the new members of the club, all Egyptian colonels of recent and miraculous promotion.

It is the Buckingham Palace Zone, but the hospitality is vaguely familiar.

In the city, everything, absolutely everything is broken, sticky or rusted. The door of the taxi which I stop, to get into town, shuts with a piece of wire. If the wheels of the bus which is following us are driven deeply into the coach work, it is probably because the suspension has gone. In spite of the showers of sparks which the fender makes, grating on the gaps in the highway, a handful of hangers on are clinging to avoid paying the conductor. At the cross-roads they jump down to catch the connection.

In a deserted construction yard, behind a jagged palisade, the skeleton of an unfinished building stands up. Some bricks, a heap of trampled sand, a rubbish dump and a pile of rusted ironwork. At the foot of a wall, a row of lavatory cisterns have been dumped, God knows why. They have simply been placed there on the ground. But the passers by have taken advantage of it and they are overflowing with shit.

Wandering from bar to bar, I very quickly make a number of friends. But really my heart is no longer in it. I've had enough of all that. Not long ago such people amused me but now they get on my nerves. I see only too well their cunning beneath all the cordiality. So I walk away shrugging my shoulders. Oh, but then, I feel I need a really good tuck-in with beef that has fed on green grass. After so much fish and rickety chicken, I just dream of it. I can't think of anything but that. I want to have a really good drink without being suspicious of the people.

Outside, in the streets of Suez, the political propaganda drips with nonsense. I remember an enormous poster, stuck on at least three stories of a dilapidated facade. A drawing showing an Egyptian soldier. At the elbow of his enormous bare arm, between the biceps and the forearm, he squeezes a tiny Israeli soldier who gesticulates with fear. Certainly I didn't realize that at that moment, the six days war was imminent.

Seen from the sea, Suez was safety, comfort and human warmth. And now comes the weariness. One only thinks of putting out to sea.

It is indeed the very last moment. We have passed the canal with one of the last convoys of ships. One week more at Suez and we would have been stuck there with no hope of returning.